第一作者简介:徐小涛,男,1992年生,博士研究生,中国矿业大学(北京)地球科学与测绘工程学院,主要从事煤田地质学和层序地层学方面的研究。E-mail: xxtawy@163.com。

近年来,根据泥质岩中常量元素的摩尔数计算出的化学蚀变指数( CIA: Chemical index of alteration)、化学风化指数( CIW: Chemical index of weathering)和斜长石蚀变指数( PIA: Plagioclase index of alteration)被广泛用来反映物源区的风化程度及物源区古气候,这些指数在应用时都有一些严格的限制因素,应给予足够重视。 CIA计算公式未排除成岩作用过程中钾交代作用的影响,需要采用 A-CN-K[ Al2O3-( CaO*+ Na2O) -K2O]三角图进行判断,对发生钾交代作用的样品利用 A-CN-K三角图或 CIAcorr计算公式进行校正。 CIW计算公式中去掉了 K2O,但没有排除钾长石中的 Al元素。 PIA计算公式中考虑了钾长石中的 Al元素,但只适用于判断母岩中仅含有斜长石而不含钾长石的物源区风化程度。综合分析表明,在判断物源区风化程度及古气候时, CIA的干扰因素相对较少,值得推广。但即使利用从泥质岩常量元素获得的 CIA值来判断物源区的风化程度时,仍需要考虑沉积分异作用、再旋回作用、沉积区进一步风化作用以及成土作用、成岩期的钾交代作用的影响,建议首先依据泥质岩常量元素的摩尔数计算出成分变异指数( ICV: Index of compositional variability),然后对 ICV> 1的样品进行 CIA的计算,并利用 A-CN-K三角图或 CIAcorr计算公式对 CIA值进行钾交代作用的校正,该校正过的 CIAcorr计算值可用来判断物源区的风化程度。

About the first author:Xu Xiao-Tao,born in 1992,is a Ph.D. candidate at College of Geoscience and Surveying Engineering of China University of Mining and Technology(Beijing). He is mainly engaged in sedimentary and sequence stratigraphy. E-mail: xxtawy@163.com.

In recent years the chemical index of alteration(CIA),chemical index of weathering(CIW)and plagioclase index of alteration(PIA), have been widely used in attempts to quantify the degree of weathering in the provenance areas and to infer paleoclimatic conditions in provenance areas. There are,however,some limiting factors in the application of these indices which merit careful consideration. The CIA does not exclude the effect of potassium metasomatism so that it is necessary to use the A-CN-K[Al2O3-(CaO*+Na2O)-K2O]triangle to identify it and make corrections,or to utilize the CIAcorr formula. The CIW provides a correction for K2O,but no allowance is made for Al in potassium feldspar. The PIA considers the Al in potassium feldspar,but is only useful to judge changes involving plagioclase feldspars. Comprehensive analyses have shown that use of the CIA is the most effective way of obtaining an estimate of weathering severity and provenance. Before utilizing CIA values to estimate the degree of weathering in the provenance area,the influences of sedimentary differentiation(grain size differences),sediment recycling,further weathering in sedimentary region,pedogenesis and potassium metasomatism should be taken into account. We recommend a procedure,that is,(1)analyzing elemental compositions of mudstones,(2)calculating an index of compositional variability(ICV),(3)selecting samples with ICV>1 and using these values for the CIA calculation,(4)using the A-CN-K ternary diagram or CIAcorr formula to correct for potassium metasomatism. The corrected CIA values can then be used to estimate the degree of weathering to which the provenance area has been subjected.

随着化学蚀变指数(CIA: Chemical index of alteration; Nesbitt and Young, 1982)、化学风化指数(CIW: Chemical index of weathering; Harnois, 1988)、斜长石蚀变指数(PIA: Plagioclase index of alteration; Fedo et al., 1995)、活动风化指数[weather(mobility)indices; Gaillardet et al., 1999]、矿物变化指数(MIA: Mineral index of alteration; Nesbitt and Markovics, 1997; Rieu et al., 2007)和风化指数(WIP: Weathering index; Parker, 1970)等概念的提出, 很多学者开始采用沉积区泥质岩的这些指数定量分析物源区的风化程度及古气候, 特别是对于重大气候事件, 如新元古代冰期(Ding et al., 2009)、晚奥陶世冰期(Young et al., 2004)、早二叠世冰期— 间冰期转变(Yang et al., 2014)、古近纪始新世— 渐新世间冰期— 冰期转变(Passchier et al., 2017)及源-汇系统(杨江海和马严, 2017)等具有重要指示作用。但是这些指数存在很多限制因素, 在应用时应谨慎对待。作者在理解CIA、CIW和PIA这3个指数的基础上, 分析了3个指数各自的限制因素, 指出了CIA在判断物源区风化程度时需要考虑的问题, 以及前人在运用CIA推测物源区风化程度时存在的问题, 最后提出了利用CIA判断物源区风化程度流程的建议。通过对于CIA、CIW和PIA的分析, 希望能够对大家更准确地判断物源区的风化程度及物源区古气候起到借鉴作用。

Wedepohl(1969)估计了上地壳矿物的体积百分数(近似值): 21%的石英、41%的斜长石和21%的钾长石。在上地壳化学风化过程中, Ca、Na和K元素逐渐从长石中析出, 导致在风化过程中, 氧化铝与碱金属的比值增高。据此, Nesbitt和Young(1982)利用地球化学的方法在研究古元古代Huronian超群泥质岩(lutites)过程中, 首次提出CIA 的概念, 并用来判断物源区的风化程度, CIA的计算公式如下:

CIA=[Al2O3/(Al2O3+CaO* +Na2O+K2O)]× 100 (1)

式中氧化物以摩尔数为单位, CaO* 是指硅酸盐矿物中的CaO, 但非硅酸盐(碳酸盐和磷酸盐)矿物中也含有CaO, 因此, 在计算CIA时需要去掉非硅酸盐矿物中的CaO。Mclennan(1993)提出间接计算CaO* 的方法: CaO剩余=CaO-P2O5× 10/3, 若CaO剩余< Na2O, 令CaO* =CaO剩余; 若CaO剩余> Na2O, 令CaO* =Na2O。通过分析得出, 高CIA值表明风化过程中Ca、Na、K等元素相对于稳定的Al和Ti元素的大量流失, 反映了温暖、潮湿气候下相对较强的风化程度; 反之, 低CIA值反映了寒冷、干燥气候下相对较弱的风化程度(Fedo et al., 1995)。Fedo等(1995)总结得出:CIA=50~60, 反映了弱的风化程度; CIA=60~80, 反映了中等风化程度; CIA=80~100, 反映了强烈风化程度。

尽管Nesbitt和Young(1982)最初提出CIA时以泥质岩为研究对象, 但是之后也被用来利用砂岩常量元素进行CIA计算并推测物源区风化程度。需要注意的是, 母岩风化产物在搬运和沉积过程中, 会发生沉积分异作用, 结果导致砂岩中保留的黏土矿物相对较少, 从而使得CIA计算值偏低, 所以, 用砂岩计算出的CIA值与用泥质岩计算出的CIA值没有可比性, 不能采用泥质岩的判断标准来分析物源区风化程度。后来有学者提出由于泥质岩具有较好的均质性和沉积后的低渗透性, 更好地保留了物源区信息, 所以泥质岩比其他碎屑岩更适合进行物源区风化程度及古气候的研究(Wronkiewicz and Condie, 1989; Nesbitt et al., 1996; Garzanti et al., 2013)。

许多学者在研究古土壤和沉积岩地球化学时发现, 沉积区的钾元素比物源区母岩中钾元素含量高, 这可能是由成岩作用过程中钾交代作用所造成的(Nesbitt and Young, 1984; Retallack, 1986; Rainbird et al., 1990)。Harnois(1988)指出CIA的计算公式中用到了K2O, 不能排除成岩作用过程中钾交代作用增加的钾元素的干扰, 为此提出CIW的概念, CIW的计算公式如下:

CIW=[Al2O3/(Al2O3+CaO* +Na2O)]× 100 (2)

式中氧化物以摩尔数为单位, CaO* 仅指硅酸盐矿物中的CaO。CIW值越高, 代表的物源区风化程度越强, 反映的物源区古气候越趋向于温暖、潮湿。

Fedo等(1995)指出CIW与CIA的计算公式相似, 差别在于CIW的计算公式中去掉了K2O, 但这种简单的转变没有考虑钾长石中的Al元素。因为CIW没有排除钾长石中的Al元素, 所以, 对于物源区母岩中钾长石富集的样品来说, 无论母岩是否经历风化作用, CIW计算值都会很高, 因而, CIW不适合判断物源区风化程度。Fedo等(1995)判断斜长石的风化程度时, 提出PIA的概念, PIA计算公式如下:

PIA=100× (Al2O3-K2O)/(Al2O3+CaO* +Na2O-K2O) (3)

式中氧化物以摩尔数为单位, CaO* 仅指硅酸盐矿物中的CaO。钾长石的分子式为K2O· Al2O3· 6SiO2, 其中Al2O3的摩尔数等于K2O的摩尔数, PIA在CIW的基础上去掉分子、分母中的K2O, 等同于去掉了钾长石中的 Al2O3, 因此PIA去掉了钾长石中的K2O和Al2O3, 仅适用于判断母岩中含有斜长石而不含钾长石的物源区风化程度。

通过对CIA、CIW和PIA这3个计算公式的综合分析得出, 在判断物源区风化程度及古气候时, CIA的干扰因素相对较少, 值得推广。

成岩作用过程中钾交代作用会带入新的钾元素, 从而导致CIA计算值偏低, 因此, 需要对其进行校正。钾交代作用可用2种方法进行校正:

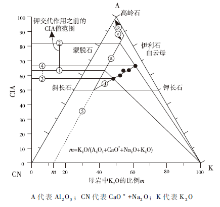

第1种方法可以用Nesbitt和Young 等提出的A-CN-K[Al2O3-(CaO* +Na2O)-K2O]三角图进行校正(Nesbitt et al., 1984; Nesbitt and Young, 1989)。图 1中近似平行于A-CN连线的实线ⓐ和实线ⓑ, 代表未发生钾交代作用的泥质岩风化趋势; 实线© 代表了高岭石向伊利石转变的过程; 实线ⓓ代表发生钾交代作用的风化趋势; ③和④之间虚线代表发生钾交代作用的泥质岩的CIA值范围; ①和②之间实线代表钾交代作用之前的CIA值范围。因此, 通过样品在A-CN-K三角图中投点的连线可以判断源区母岩风化产物在成岩作用过程中是否发生钾交代作用, 并且通过K端元与样品点连线的反向延伸线与为未发生钾交代作用风化趋势的实线ⓐ的交点值, 即代表钾交代作用之前的泥质岩的CIA值(Fedo et al., 1995; Panahi et al., 2000)。

| 图 1 A-CN-K三角简图 (据Fedo et al., 1995; Panahi et al., 2000修改)Fig.1 A-CN-K ternary diagram (modified from Fedo et al., 1995; Panahi et al., 2000) |

第2种方法可以用Panahi等(2000)提出的CIAcorr公式进行校正, 进而计算出未发生钾交代作用的泥质岩的CIA值(CIAcorr)。计算公式如下:

CIAcorr=[Al2O3/(Al2O3+CaO* +Na2O+K2Ocorr)]× 100 (4)

K2Ocorr=[m· Al2O3+m· (CaO * +Na2O)]/(1-m) m=K2O/(Al2O3+CaO* +Na2O+K2O)

式中氧化物以摩尔数为单位, CaO* 仅指硅酸盐矿物中的CaO, 不包含非硅酸盐(碳酸盐和碳酸盐)矿物中含有的CaO; K2Ocorr的计算值为未发生钾交代作用的泥质岩中K2O的含量; m代表母岩中K2O的比例。母岩中K2O的比例m值还可通过图1得到, 图 1中近似平行于A-CN连线的实线ⓐ的延长虚线⑤与CN-K坐标轴的交点即m值。

通过以上2种方法可以得出钾交代作用之前的泥质岩的CIA值。

现实中物源区母岩物质是复杂的, 用CIA定量分析物源区的风化程度及古气候时, 还应该考虑到一些其他地质因素的影响。

物源区母岩风化产物在搬运和沉积过程中, 会发生沉积分异作用, 从而导致砂岩中黏土矿物含量相对较少。研究发现, 砂岩常量元素可用来进行CIA计算并推测物源区风化程度, 但用砂岩计算出的CIA值不能采用泥质岩的CIA判断标准。

已有的许多文献在利用CIA分析物源区风化程度时, 对沉积分异作用的影响没有给予足够的重视, 通过砂岩计算得出的CIA值没有与同种粒度的砂岩标准进行比较(Armstrong-Altrin et al., 2004; Fadipe et al., 2011; Perri, 2014; Awasthi, 2017), 因此, 得出的物源区风化程度不够准确。

再旋回的母岩物质在经历二次风化后, 会导致CIA值偏大, 从而不能准确地反映源区风化程度及古气候。Cox等(1995)研究再旋回过程中泥质岩的化学特征时, 提出成分变异指数(ICV: Index of compositional variability), 并用来判断物源区物质是否发生再旋回作用。ICV的计算公式如下:

ICV=(Fe2O3+K2O+Na2O+CaO+MgO+MnO+TiO2)/A12O3 (5)

式中氧化物以摩尔数为单位。因为非黏土硅酸盐矿物中A12O3的含量低于黏土矿物中的含量, 所以非黏土硅酸盐矿物的ICV值大于黏土矿物的ICV值。同时也可用ICV值来判断泥质岩的成分成熟度, ICV< 1, 说明成熟的样品中含有较高的高岭石、蒙脱石和绢云母等黏土矿物成分, 代表可能经历了再旋回作用或首次沉积条件下经历了强烈的风化作用(Barshad, 1966); ICV> 1, 说明未成熟的泥质岩中含有较高的非黏土硅酸盐矿物, 属于构造活动背景下的首次沉积(Kamp and Leake, 1985)。通过CIA判断物源区的风化程度及古气候时, 如果选取ICV< 1的样品, 无法排除再旋回作用的影响, 应该选取ICV> 1的样品, 从而排除再旋回作用对CIA计算的影响。

通过计算ICV排除再旋回作用已被重视(冯连君等, 2003; Ding et al., 2009; Perri and Ohta, 2014; 雷开宇等, 2017; Perri, 2017), 但是许多学者利用CIA值推测物源区风化程度时, 对再旋回作用的影响仍然考虑不够充分(Fadipe et al., 2011; Jayaprakash et al., 2012; Armstrong-Altrin et al., 2013; 罗情勇等, 2013; Effoudou-Priso et al., 2014; Perri, 2014; Varma et al., 2017; 付亚飞等, 2018), 所获得的关于物源区风化程度的结论欠准确。

Young和Nesbitt(1999)研究古元古代Huronian超群Gowganda组时, 把样品投到A-CN-K三角图上发现, 一部分样品的CIA值在50左右, 其中长石含量较多, 黏土矿物含量较少, 物源可能来自于冰川作用的太古代上地壳; 另一部分样品的CIA值在70左右, 研究认为, 这部分样品来自元古代的风化壳, 由于沉积区气候温暖湿润, 物源区母岩的风化产物在沉积区再次经历风化作用, 从而使CIA的计算值偏大。通过分析得出, 如果泥质岩在沉积区经历进一步风化作用, 会导致CIA值偏大, 从而不能准确反映物源区的风化程度。

风化壳是指在地质历史时期中, 暴露于地表的地层经历风化作用而形成的古土壤和松散的残积物。在层序地层学中, 不整合面作为层序界面的典型代表, 表明发生过沉积间断, 而河道之间不整合面上的古土壤层一般是经历成土作用而成, 表明岩石在沉积区经历进一步风化作用。如果选取不整合界面上的古土壤作为研究对象, 会导致CIA值偏大, 从而影响对物源区风化程度的准确判断。

根土岩是指煤层底板发育植物根的泥质岩, 相当于现代的潮湿气候下的潜育土, 是地表暴露的一个主要标志, 代表了一段时间的沉积间断(邵龙义等, 2005)。古土壤层表明岩石在沉积区经历成土作用并遭受淋滤作用, 这种淋滤作用会导致Ca、Na、K等元素进一步流失, 但与物源区的风化作用没有任何关系, 因此使用经历过淋滤作用的古土壤泥质岩的化学成分计算的CIA值不能反映物源区风化作用。此外, 成土作用过程中生物活动和植物根系分泌的有机酸亦会影响到古土壤的风化(Egli et al., 2001, 2008; Wilson, 2004; Skiba, 2007), 这些影响显然也不是物源区风化作用的结果。总之, 根土岩经历了复杂的地质历史作用, 因此不能仅凭简单的地球化学分析, 来反映物源区的风化程度及古气候。此外, 物源区的岩浆岩与上覆古土壤层的CIA会有明显不同, 反映出同一风化壳不同深度的古土壤所代表的风化作用程度明显不同, 例如Szymań ski和Szkaradek(2018)所研究的安山岩及其上覆的古土壤层。

对于沉积区进一步风化作用及成壤作用, 同样可以用ICV计算公式(5)判断, 但是目前许多利用CIA值判断物源区风化程度的文献, 多没有对所使用的样品是否在沉积区经历进一步风化作用给予充分考虑, 如果选取沉积区的风化壳(

通常情况下, 物源区母岩在风化过程中钾元素逐渐减少, 如果在成岩作用过程中发生钾交代作用, 会使钾元素增多, 从而导致CIA值偏小, 因此, 需要利用A-CN-K三角图或CIAcorr计算公式进行钾交代作用的校正。但已有的很多文献用CIA值判断物源区风化程度时, 并没有对成岩作用过程中钾交代作用判断和校正(Fadipe et al., 2011; Jayaprakash et al., 2012; 付亚飞等, 2017), 从而使推测的物源区风化程度不够准确。

现代海洋沉积物中的主要黏土矿物组合, 在不同纬度呈现明显的规律性: ①高岭石、铝土矿和蒙脱石主要分布在热带潮湿地区, 并且向南北两极逐渐减少, 这种分布称为赤道类型分布; ②绿泥石和伊利石主要分布在中等湿润和寒冷地区(中、高纬度), 这种分布称为两极类型分布(Fagel, 2007)。

从全球角度来看, 不同纬度的黏土矿物组合确实存在差异, 而同一地区不同沉积环境下的黏土矿物组合也会存在差异。由于黏土矿物化学分异作用的影响, 在酸性的水介质中, 高岭石的稳定程度大于蒙脱石, 蒙脱石向高岭石转化; 在碱性的水介质中, 蒙脱石比较稳定, 高岭石则向蒙脱石、伊利石转化, 从而导致不同的环境中形成不同的黏土矿物组合。另外, 盐度可以控制黏土矿物的差异絮凝作用, 高岭石趋于在较低盐度的介质中絮凝沉降, 从而多沉积在接近河口处, 伊利石则趋于在较高盐度中沉降, 多沉积在远离河口处, 同样导致不同沉积环境中产生不同的黏土矿物组合(Edzwald and O’ Melia, 1975; 邵龙义和张鹏飞, 1992; 赵永胜, 1993; 罗忠等, 2008)。机械分异作用对黏土矿物的组合也会产生影响, 由于高岭石、伊利石的粒径比蒙脱石的粒径大, 因此在沉积过程中, 高岭石和伊利石向海方向减少, 而蒙脱石反而增加(何良彪, 1984; 吕全荣和王效京, 1985; 赵永胜, 1993)。

全球不同纬度的黏土矿物组合存在差异, 并且化学分异作用和机械分异作用也都会导致不同环境下黏土矿物组合的差异性, 这些差异都会对CIA的计算结果造成影响(表 1)。因此, 在通过CIA值判断物源区风化程度及物源区古气候时, 尽量选取同一沉积环境中的样品进行CIA的计算, 从而减少不同环境中黏土矿物组合差异性的干扰。

| 表 1 不同黏土矿物的CIA值范围 (化学式来自常丽华等, 2006) Table1 CIA value range of different clay minerals (chemical formulas from Chang et al., 2006) |

Nesbitt和Young(1982)提出CIA的概念, 并用来判断物源区的风化程度, 但母岩在风化、搬运和沉积过程中, 经历的沉积分异作用、再旋回作用、沉积区进一步风化作用以及成土作用、成岩期的钾交代作用都会对CIA的计算造成影响。只有排除这些限制因素, 才能确保CIA值判断物源区风化程度的准确性, 建议流程如图 2所示。

经过对上述限制因素的讨论, 建议首先依据泥质岩常量元素的摩尔数计算出ICV值, 然后对ICV> 1的样品进行CIA的计算, 并利用A-CN-K三角图或CIAcorr计算公式对CIA值进行成岩作用过程中钾交代作用的校正, 该校正后的CIAcorr计算值可用来判断物源区的风化程度。

1)在判断物源区风化程度时, CIW计算公式中去掉了K2O, 但没有排除钾长石中的Al元素, PIA考虑了钾长石中的Al元素, 但仅适用判断母岩中含有斜长石而不含钾长石的物源区风化程度, 而CIA干扰因素相对较少, 值得推广。

2)采用CIA判断源区的风化程度时, 需要注意沉积分异作用、再旋回作用、沉积区的进一步风化作用以及成壤作用、成岩期的钾交代作用的影响。

3)采用CIA判断物源区的风化程度时, 建议首先依据泥质岩常量元素的摩尔数计算出ICV值, 然后对ICV> 1的样品进行CIA的计算, 并利用A-CN-K三角图或CIAcorr计算公式对CIA值进行钾交代作用的校正, 该校正后的CIAcorr计算值可用来判断物源区的风化程度。

致谢 成文过程中, Grant Young教授对关键问题给予悉心指导与热情帮助, 在此谨致谢意!

作者声明没有竞争性利益冲突.

| [1] |

|

| [2] |

|

| [3] |

|

| [4] |

|

| [5] |

|

| [6] |

|

| [7] |

|

| [8] |

|

| [9] |

|

| [10] |

|

| [11] |

|

| [12] |

|

| [13] |

|

| [14] |

|

| [15] |

|

| [16] |

|

| [17] |

|

| [18] |

|

| [19] |

|

| [20] |

|

| [21] |

|

| [22] |

|

| [23] |

|

| [24] |

|

| [25] |

|

| [26] |

|

| [27] |

|

| [28] |

|

| [29] |

|

| [30] |

|

| [31] |

|

| [32] |

|

| [33] |

|

| [34] |

|

| [35] |

|

| [36] |

|

| [37] |

|

| [38] |

|

| [39] |

|

| [40] |

|

| [41] |

|

| [42] |

|

| [43] |

|

| [44] |

|

| [45] |

|

| [46] |

|

| [47] |

|

| [48] |

|

| [49] |

|

| [50] |

|

| [51] |

|

| [52] |

|

| [53] |

|

| [54] |

|

| [55] |

|

| [56] |

|

| [57] |

|

| [58] |

|